For Mailer, boxing was a metaphor for life, for writing, for the eternal struggle of man against man, and man against himself.

Picture this: It’s 1923, and little Norman pops into the world in Long Branch, New Jersey. But don’t let that fool you – he’s Brooklyn to the bone, raised in the concrete jungle where dreams are made and egos are inflated to the size of the Empire State Building.

Now, Mailer wasn’t your average Joe. This kid had brains, and he wasn’t shy about it. By the time he hit Harvard at 16, he was already quite the prolific young writer. At 18, he published his first story: “The Greatest Thing in the World,”which scored him a win in Story Magazine’s college writing contest.

But here’s where it gets interesting. World War II comes knocking, and Mailer answers the call. He serves in the Philippines, and let me tell you, it wasn’t all sunshine and coconuts. This experience? It’s like lighting a stick of dynamite in his mind. Boom! Out comes “The Naked and the Dead” in 1948, when Mailer’s just 25 years old. And it’s not just a novel. It’s a literary atomic bomb. In fact, if you read ONE war novel in your life, please read this one.

Fun fact: While stationed in Japan, Mailer wrote more than 400 letters to his wife, Bea. And I just learned this tidbit while researching him for this article – he used those as the starting point for “The Naked and the Dead.” I love this because I’m a huge fan of letter writing as a creative format all its own (side note: Hemingway’s letters to F. Scott Fitzgerald are fascinating)

So it’s 1948, and suddenly, Mailer’s the toast of the town. The golden boy of American letters. But does he rest on his laurels? Hell no! That’s not the Mailer way. He’s like a shark – always moving, always hungry. He dives into journalism, politics, film-making. He’s not just writing about life; he’s living it, breathing it, sometimes fighting it (literally – the man had a mean right hook).

Mailer writes like he’s actually in a boxing match with language itself.

Now, let’s talk about his style. Mailer writes like he’s actually in a boxing match with language itself. His sentences jab, hook, and uppercut. They’re long, they’re short, they’re thrilling. The guy could type. He was also a fighter, and that showed in his ink.

Mailer and Boxing

Speaking of fighting, let’s step into the ring for a moment. Mailer wasn’t just a writer who used boxing metaphors – he was a genuine fight aficionado. His love affair with the sweet science started in his youth, watching fights with his father. But it wasn’t until he was in his forties that he really dove headfirst into the world of jabs and uppercuts.

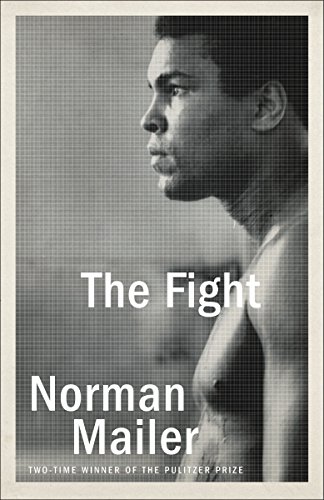

In 1971, Mailer covered the “Fight of the Century” between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier for Life magazine. His article, later expanded into the book “The Fight,” wasn’t just a blow-by-blow account. It was a masterpiece of sports writing that captured the drama, the personalities, and the cultural significance of the event. Mailer didn’t just watch the fight; he lived it, breathed it, and translated it into prose that hit as hard as Ali’s left hook.

But Mailer didn’t stop at writing about boxing. Oh no, that wasn’t his style. He stepped into the ring himself, sparring with pros and amateurs alike. Picture this: a short, stocky writer in his fifties, trading punches with guys half his age. That was Mailer – always in the thick of things, always pushing himself to the limit.

His obsession with boxing wasn’t just about the physical aspect, though. For Mailer, boxing was a metaphor for life, for writing, for the eternal struggle of man against man, and man against himself. He saw in boxing a raw, primal truth that he strived to capture in his writing. The sport influenced his prose style, his approach to conflict, and his view of masculinity. He had much in common with Hemingway that way.

Mailer’s influence on the boxing world was significant. His writing helped elevate boxing journalism to an art form. He didn’t just report on fights; he explored the psychological depths of the fighters, the socio-economic contexts of the sport, and its place in the broader cultural landscape. After Mailer, boxing writing was never the same. In fact, what the boxing world needs right now is a contemporary Norman Mailer.

He’d argue with anyone about anything – politics, literature, the best way to make a martini. And boy, did he have opinions.

Far from the stereotype of the reclusive, pensive writer, Mailer was a character in his own right. Picture a short, stocky guy with a mop of unruly hair and eyes that could burn a hole through steel. He didn’t just attend parties; he was the party. He’d argue with anyone about anything – politics, literature, the best way to make a martini. And boy, did he have opinions.

Take his views on women, for instance. Let’s just say they were… complicated. He once said, “A little bit of rape is good for a man’s soul.” Yikes, right? But that’s Mailer for you – always pushing buttons, always courting controversy. He was a man of his time, for better or worse, and he never shied away from the uglier aspects of human nature.

But don’t think for a second that Mailer was all bluster and no substance. This man had range. He could write about anything – war, politics, sex, murder, even ancient Egypt. His book “The Executioner’s Song” won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1980. It’s a true-crime novel about Gary Gilmore, a convicted murderer who demanded his own execution. Heavy stuff, but Mailer handles it with the grace of a tightrope walker and the raw power of a heavyweight champ.

And let’s not forget “Armies of the Night,” his account of the 1967 anti-Vietnam War march on Washington. Mailer doesn’t just report on the event; he throws himself into it, getting arrested and becoming part of the story. It’s gonzo journalism before Hunter S. Thompson made it cool, and it won Mailer another Pulitzer.

But here’s the thing about Mailer – he wasn’t just a writer. He was a cultural icon, a living, breathing embodiment of the American century. He ran for mayor of New York City (and came in fourth out of five candidates). He co-founded The Village Voice, one of the first alternative newspapers in America. He made films, he boxed, he drank, he argued, he lived life like it was going out of style.

And through it all, he kept writing. Novel after novel, essay after essay. Some were hits, some were misses, but all of them had that unmistakable Mailer flair. He was like a literary Elvis – even when he wasn’t at his best, he was still the King.

Now, I’m not gonna sugarcoat it – Mailer had his demons. He struggled with alcohol, he had tumultuous relationships (six marriages!), and he once stabbed one of his wives with a penknife. Not cool, Norman. Not cool at all. But that’s the thing about great writers – they’re often flawed, complicated people. And Mailer? He was as complicated as they come.

Mailer’s writing is a shot of adrenaline straight to the brain. He doesn’t just tell you a story; he grabs you by the collar and drags you into it.

But here’s why you should care about Norman Mailer. In a world of bland, cookie-cutter prose, Mailer’s writing is a shot of adrenaline straight to the brain. He doesn’t just tell you a story; he grabs you by the collar and drags you into it. Whether you love him or hate him (and trust me, people did both), you can’t ignore him.

So, if you’re looking for a literary adventure, pick up a Mailer book. Start with “The Naked and the Dead” or maybe “The Armies of the Night” if you want to see how crazy the ’60s really were. If you want to skip right to a boxing book, definitely get a copy of “The Fight.” In fact, if you’re a boxer, or a boxing fan, you MUST read this one.

Reading Mailer is not for the faint of heart. It’s a wild ride, full of brilliant insights, outrageous opinions, and gorgeous prose.

In the end, that’s what Mailer was all about – the thrill of the fight, the joy of the written word, the endless struggle to capture the American experience in all its glory and madness. He passed away in 2007, but his words? They’re still out there, still swinging, still ready to knock you out.