“My writing is nothing, my boxing is everything”

– Ernest Hemingway

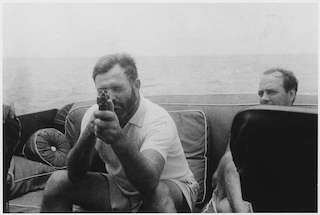

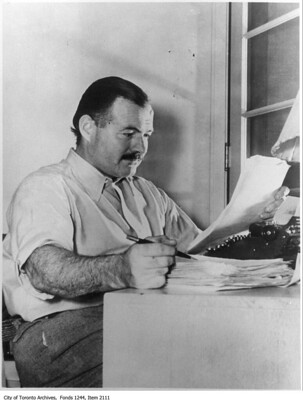

Writers have long held a certain obsession with boxing. There’s something about the poetry of a ring that appeals to us intellectually, emotionally, and even spiritually. Ernest Hemingway, known for his terse prose and larger-than-life persona, had an intimate connection with the world of boxing that permeated his writing, perhaps like no other writer (outside of Norman Mailer, arguably). His fascination with boxing did not arise solely from his love for the sport, but also from his own experiences in the ring, both as a youth and well into his fifties. And while many literary critics have enjoyed taking jabs at the late novelist for his failures; for his lack of skill in the ring, for his bravado, and perhaps even some misplaced machismo, keep this in mind: none of them can box, and none of them can write novels.

I don’t agree at all with Hemingway’s critics who claim he pursued boxing specifically to make up for his insecurity or lack of masculinity, or to prove a point. Did he perhaps have an unrealistic and romantic view of boxing? Of course. Did he imagine himself more accomplished in the sport than he actually was? No doubt. Did he act foolishly when he sparred with real fighters who constantly knocked him down – and sometimes out? Yes, and yes. None of these things matter. What matters is that Hemingway, for all his human flaws, was a visionary. He was masterful at his craft, and he used boxing as fuel for his storytelling in a way that only he could. Boxing is woven through so many of his works that it would be hard to imagine Hemingway’s work without it, and I wouldn’t want to. The fact he had little fighting skill in real life, or that he talked a lot of shit (which is actually a typical trait in most fighters) only adds to his literary charm.

Boxing is the Physical Expression of Hemingway’s Writing Style

Just as a boxer relies on quick jabs and powerful hooks to convey their strength and skill, Hemingway employed short, declarative sentences and sparse dialogue to create an immediate and visceral experience for the reader. His prose was stripped down to its bare essentials, much like the movements of a skilled pugilist in the ring. This stripped-down style allowed Hemingway to convey emotion and meaning through action rather than excessive description. But the author of A Farewell to Arms employed his style so masterfully that his short jabs of prose convey more meaning and emotion than the lengthy descriptions of his contemporaries. Take, for example, the following lines from Hemingway’s 1926 story, In Another Country:

“In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it anymore.” It’s one short sentence, but in that sentence is an entire world.

In Hemingway’s literary universe, boxing served as a powerful symbol for the human condition. It’s even mentioned in the very first lines of The Sun Also Rises:

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing, in fact he disliked it, but he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton. There was a certain inner comfort in knowing he could knock down anybody who was snooty to him, although, being very shy and a thoroughly nice boy, he never fought except in the gym. He was Spider Kelly’s star pupil. Spider Kelly taught all his young gentlemen to box like featherweights, no matter whether they weighed one hundred and five or two hundred and five pounds. But it seemed to fit Cohn. He was really very fast. He was so good that Spider promptly overmatched him and got his nose permanently flattened. This increased Cohn’s distaste for boxing, but it gave him a certain satisfaction of some strange sort, and it certainly improved his nose. In his last year at Princeton he read too much and took to wearing spectacles. I never met any one of his class who remembered him. They did not even remember that he was middleweight boxing champion.

Through boxing, Hemingway explored themes of masculinity, courage, and the inherent struggle of existence. Just as a boxer must assert his dominance and prove his skill in a fight, Hemingway’s characters grapple with their own notions of masculinity, always in search of their place in a chaotic world. So did their author. Still, Hemingway showed genuine courage every time he stepped into a ring, even if he was usually getting himself KO’d by Morley Callaghan, or struggling on the ropes with the likes of Gene Tunney.

Everyone Fights Alone, Especially Writers

Being a writer is a constant battle, mostly with yourself. You show up, give it your all, and you either win or lose that day. Boxing is the same. Even if you’re facing an opponent, even if you’re surrounded by trainers and have the best men in your corner plus a crowd of fans, you go into the fight alone. Every man fights alone, and every author writes alone.

So, let the critics say what they will about Hemingway’s lack of ability inside the ropes, or point at his self-aggrandizing machismo. The fact remains that boxing was in Hemingway; it was part of him. Perhaps because of this, his words landed on the page like a flurry of straight shots down the middle. In every novel and every short story, throughout his writing career, he remained undefeated.

And the crowd went wild.